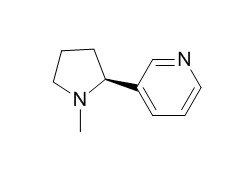

L-Nicotine

Nicotine is a potent inhibitor of cardiac A-type K+ channels, with blockade probably due to block of closed and open channels, this action may contribute to the ability of nicotine to affect cardiac electrophysiology and induce arrhythmias.Nicotine is able to activate mitogenic signalling pathways, which promote cell growth or survival as well as increase chemoresistance of cancer cells, nicotine activates its downstream signalling to interfere with the ubiquitination process and prevent Bcl-2 from being degraded in lung cancer cells, resulting in the increase of chemoresistance.

Inquire / Order:

manager@chemfaces.com

Technical Inquiries:

service@chemfaces.com

Tel:

+86-27-84237783

Fax:

+86-27-84254680

Address:

1 Building, No. 83, CheCheng Rd., Wuhan Economic and Technological Development Zone, Wuhan, Hubei 430056, PRC

Providing storage is as stated on the product vial and the vial is kept tightly sealed, the product can be stored for up to

24 months(2-8C).

Wherever possible, you should prepare and use solutions on the same day. However, if you need to make up stock solutions in advance, we recommend that you store the solution as aliquots in tightly sealed vials at -20C. Generally, these will be useable for up to two weeks. Before use, and prior to opening the vial we recommend that you allow your product to equilibrate to room temperature for at least 1 hour.

Need more advice on solubility, usage and handling? Please email to: service@chemfaces.com

The packaging of the product may have turned upside down during transportation, resulting in the natural compounds adhering to the neck or cap of the vial. take the vial out of its packaging and gently shake to let the compounds fall to the bottom of the vial. for liquid products, centrifuge at 200-500 RPM to gather the liquid at the bottom of the vial. try to avoid loss or contamination during handling.

Environ Toxicol.2023, tox.23999.

South African J of Plant&Soil2018, 29-32

Research Square2021, 10.21203.

Nat Prod Sci.2018, 24(2):109-114

Environ Toxicol.2024, 39(4):2417-2428.

ScienceAsia2024, 50,2024073:1-9

J Cell Mol Med.2023, 27(11):1592-1602.

Molecules.2023, 28(8):3503.

Heliyon.2023, e12778.

Biomed Pharmacother.2024, 173:116319.

Related and Featured Products

Anal Bioanal Chem. 2013 Aug;405(20):6479-87.

Molecularly imprinted polymers as synthetic receptors for the QCM-D-based detection of L-nicotine in diluted saliva and urine samples.[Pubmed:

23754330]

Molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) are synthetic receptors that are able to specifically bind their target molecules in complex samples, making them a versatile tool in biosensor technology. The combination of MIPs as a recognition element with quartz crystal microbalances (QCM-D with dissipation monitoring) gives a straightforward and sensitive device, which can simultaneously measure frequency and dissipation changes.

METHODS AND RESULTS:

In this work, bulk-polymerized L-Nicotine MIPs were used to test the feasibility of L-Nicotine detection in saliva and urine samples. First, L-Nicotine-spiked saliva and urine were measured after dilution in demineralized water and 0.1× phosphate-buffered saline solution for proof-of-concept purposes. L-Nicotine could indeed be detected specifically in the biologically relevant micromolar concentration range. After successfully testing on spiked samples, saliva was analyzed, which was collected during chewing of either nicotine tablets with different concentrations or of smokeless tobacco.

CONCLUSIONS:

The MIPs in combination with QCM-D were able to distinguish clearly between these samples: This proves the functioning of the concept with saliva, which mediates the oral uptake of nicotine as an alternative to the consumption of cigarettes.

Anal Bioanal Chem. 2013 Aug;405(20):6453-60.

Heat-transfer-based detection of L-nicotine, histamine, and serotonin using molecularly imprinted polymers as biomimetic receptors.[Pubmed:

23685906]

METHODS AND RESULTS:

In this work, we will present a novel approach for the detection of small molecules with molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP)-type receptors. This heat-transfer method (HTM) is based on the change in heat-transfer resistance imposed upon binding of target molecules to the MIP nanocavities. Simultaneously with that technique, the impedance is measured to validate the results. For proof-of-principle purposes, aluminum electrodes are functionalized with MIP particles, and L-Nicotine measurements are performed in phosphate-buffered saline solutions. To determine if this could be extended to other templates, histamine and serotonin samples in buffer solutions are also studied. The developed sensor platform is proven to be specific for a variety of target molecules, which is in agreement with impedance spectroscopy reference tests. In addition, detection limits in the nanomolar range could be achieved, which is well within the physiologically relevant concentration regime. These limits are comparable to impedance spectroscopy, which is considered one of the state-of-the-art techniques for the analysis of small molecules with MIPs. As a first demonstration of the applicability in biological samples, measurements are performed on saliva samples spiked with L-Nicotine.

CONCLUSIONS:

In summary, the combination of MIPs with HTM as a novel readout technique enables fast and low-cost measurements in buffer solutions with the possibility of extending to biological samples.

Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1989;99(2):208-12.

Discriminative stimulus effects of intravenous l-nicotine and nicotine analogs or metabolites in squirrel monkeys.[Pubmed:

2508155]

METHODS AND RESULTS:

Squirrel monkeys were trained to emit one response after IV administration of L-Nicotine (0.4 or 0.2 mumol/kg) and a different response after IV administration of saline. After stable discriminative performances were established, subjects were tested with cumulative doses of L-Nicotine (0.02-2.2 mumol/kg), d-nicotine (0.02-19.7 mumol/kg), l-nornicotine (0.2-12.0 mumol/kg), l-cotinine (56.8-567.5 mumol/kg), and dl-anabasine (0.6-19.7 mumol/kg). All of the drugs produced dose-related increases in the percentage of drug-appropriate responses emitted, from predominantly saline-appropriate responses after low doses, to predominantly drug-appropriate responses at the highest doses studied. Relative potency comparisons indicated that L-Nicotine was 28 times more potent than d-nicotine, 29 times more potent than l-nornicotine, and approximately 2000 times more potent than l-cotinine. Each of the drugs also produced decreases in rates of responding, with potency order similar to that obtained for the discriminative effects.

CONCLUSIONS:

The effects of l-cotinine may be attributed to trace amounts of L-Nicotine, which existed within the l-cotinine. The effects of dl-anabasine were lethal in one subject and were consequently not studied in the other subjects.

Microbiology. 2009 Jun;155(Pt 6):1866-77.

Uptake of L-nicotine and of 6-hydroxy-L-nicotine by Arthrobacter nicotinovorans and by Escherichia coli is mediated by facilitated diffusion and not by passive diffusion or active transport.[Pubmed:

19443550 ]

The mechanism by which L-Nicotine is taken up by bacteria that are able to grow on it is unknown.

METHODS AND RESULTS:

Nicotine degradation by Arthrobacter nicotinovorans, a Gram-positive soil bacterium, is linked to the presence of the catabolic megaplasmid pAO1. l-[(14)C]Nicotine uptake assays with A. nicotinovorans showed transport of nicotine across the cell membrane to be energy-independent and saturable with a K(m) of 6.2+/-0.1 microM and a V(max) of 0.70+/-0.08 micromol min(-1) (mg protein)(-1). This is in accord with a mechanism of facilitated diffusion, driven by the nicotine concentration gradient. Nicotine uptake was coupled to its intracellular degradation, and an A. nicotinovorans strain unable to degrade nicotine (pAO1(-)) showed no nicotine import. However, when the nicotine dehydrogenase genes were expressed in this strain, import of l-[(14)C]nicotine took place. A. nicotinovorans pAO1(-) and Escherichia coli were also unable to import 6-hydroxy-L-Nicotine, but expression of the 6-hydroxy-L-Nicotine oxidase gene allowed both bacteria to take up this compound. L-Nicotine uptake was inhibited by d-nicotine, 6-hydroxy-L-Nicotine and 2-amino-L-Nicotine, which may indicate transport of these nicotine derivatives by a common permease. Attempts to correlate nicotine uptake with pAO1 genes possessing similarity to amino acid transporters failed.

CONCLUSIONS:

In contrast to the situation at the blood-brain barrier, nicotine transport across the cell membrane by these bacteria was not by passive diffusion or active transport but by facilitated diffusion.